Shelby County is on the eastern boundary of the state, in a bulge of the Sabine River that separates it from Desoto and Sabine parishes in Louisiana. The county is bounded on the south by San Augustine and Sabine counties, on the west by Rusk and Nacogdoches counties, and on the north by Panola County. The county seat and largest town is Center, which is 160 miles northeast of Houston and forty miles northeast of Nacogdoches. Center is named for its location at the geographic center of the county, which lies at 31°47′ north latitude and 94°11′ west longitude. Two major highways cross the county, U.S. Highway 96, which traverses the center of the county from north to south, and U.S. Highway 84, which traverses the northern portion of the county from east to west. The county’s transportation needs are also served by two railroads, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, which traverses the county along the route of Highway 96, and the Southern Pacific, which follows roughly the same route as Highway 84. Shelby County comprises 791 square miles of the East Texasqv timberlands, an area that is heavily forested with a great variety of softwoods and hardwoods, especially pine, cypress, and oak. The terrain varies from undulating to rolling with elevation ranging from 150 to 400 feet above mean sea level. The soil varies from a gray sandy loam on the uplands to a black rich loam in the bottom lands. Between 21 and 30 percent of the land in the county is considered prime farmland. The climate is moist and mild with temperatures that range from an average high of 94° F in July to an average low of 34° in January and an average annual rainfall of fifty inches. The growing season extends for an annual average of 240 days. Most of the county is drained by the Sabine River, but some of the western portion is drained by the Neches River. Mineral resources include lignite coal, sand, oil, and gas. Pine and hardwood production in 1981 totalled 14,867,416 cubic feet, the overwhelming majority of which was pine production.

Shelby County is in an area that has been the site of human habitation for several thousand years. Archaeological artifacts have been recovered from the area around Sam Rayburn Reservoir in Sabine County. During historic times the area was occupied for the most part by Caddo Indians, an agricultural people with a highly developed culture. Earliest European exploration of the area that would become Shelby County cannot be conclusively determined. If one of the southernmost of the numerous conflicting route interpretations of the Moscoso expedition in 1542 is correct, then that group passed through or very near the area of Shelby County. It could be, however, that first European contact with the area did not occur until the eighteenth century. French and Spanish explorers discovered and utilized traces of an east-west Hasinai Indian trail, which, after 1714, became a part of El Camino Real or the Old San Antonio Road. The road ran through the area of Sabine and San Augustine counties, just south of Shelby County. In 1716 Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Ais Mission was founded just south of the site of present San Augustine. Although the mission was abandoned for a short period, it remained in existence until 1773. During this period the Spanish probably explored the area comprising present-day Shelby County. Sometime during the second decade of the nineteenth century John Latham, reputedly the first settler, settled in the southeastern part of the county in 1818. Mexican restrictions forbidding settlements within twenty leagues of the boundary of Texas curtailed legitimate settlement and encouraged squatters. Consequently, the area gained a reputation for violence and remained scarcely populated.

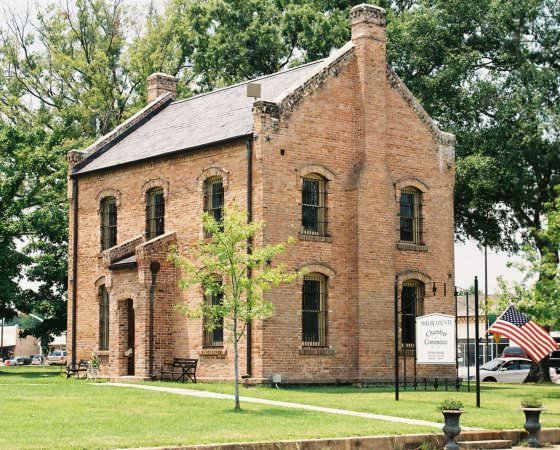

Shelby County was first organized under the Mexican government as Tenehaw Municipality; Nashville, founded in 1824, was the most important town. In 1836 the Congress of the Republic of Texas established Shelby County, named for Isaac Shelby, hero of the American Revolution and governor of Kentucky. The name of the town Nashville was changed to Shelbyville, and Shelbyville became the county seat, which it remained until 1866, when the county seat was moved to Center. Since that time Center has remained the county seat. The courthouse in Center, along with all county records, was destroyed by fire in 1882. A new courthouse, modeled on an Irish castle, was designed by the architect John Joseph Emmett Gibson, an Irish immigrant. It was completed in 1885 and was recognized in the National Register of Historic Places in 1971. The courthouse still housed the county government in 1984. In 1840 disputes over land titles and fraudulent land transactions led to the opposition of two factions, the Regulators and the Moderators, and a series of armed conflicts that came to be known as the Regulator-Moderator War. Before the conflict was finally resolved in 1844, a number of the individuals involved were killed or tried and hanged, and the economy of Shelby County seems to have been devastated. The effects of the war on the county’s economy and growth do not appear to have been permanent. By 1847 the county had a population of 3,318, which was only marginally lower than San Augustine County to the south and Panola County to the north. Between 1847 and 1860 Shelby County continued to grow to 4,239 and 5,362, recorded in 1850 and 1860, respectively.

During the antebellum period the county was, for the most part, rural and agricultural, with most of the county’s residents living on farms. The largest crop of any kind and the most important food crop was corn. County farmers produced 99,518 bushels in 1850. Farmers also grew 9,805 bushels of oats. The largest cash crop was cotton, but farmers produced just 790 bales in 1850. Livestock was also important to the county’s economy. The more than 20,000 hogs in the county were a major food source, as were the 10,000 cattle. During the 1850s arable production expanded much more rapidly than did the population of the county. By 1860 the corn crop had risen by 70 percent, increasing to 167,475 bushels, while the cotton crop was a little more than five times larger than the 1850 crop with production totalling 4,052 bales. Livestock production did not change so dramatically. The number of hogs and cattle in the county declined slightly, but sheep production grew from an 1850 total of 1,296 and 1,770 pounds of wool to 2,794 sheep and 7,408 pounds of wool by 1860.

Shelby County’s inhabitants overwhelmingly supported the secession movement during the winter of 1860–61. When the secession ordinance was submitted for popular approval in February of 1861, county voters approved the measure by a vote of 333 to 28. They also wholeheartedly supported the war effort of the Confederacy that followed. One county source estimated that as many as 750 men from Shelby County served in either state or Confederate army units. Shelby County was never occupied by Union forces, and thus escaped the destruction which devastated other parts of the South. Nonetheless, the war years were difficult for the county’s citizens. They were forced to deal with the lack of markets and wild fluctuations in Confederate currency, as well as concern for those on the battlefield. The end of the war meant wrenching changes in the county’s economy. The postwar era brought freedom for the county’s black population. In 1910 almost one-third (160 out of 541) of all black farmers were landowners.

For more than six decades after the Civil War Shelby County remained rural and agricultural as it had been during the antebellum period. The number of farms in the county rose each census year through 1940, as did the population. In 1870 the population of the county was 5,732, and there were 820 farms; by 1940 the population had risen to 29,235 and the number of farms to 4,952. Just as during the antebellum period, the principal food crop was corn, and the principal cash crop was cotton. Each census year between two-thirds and nine-tenths of all harvested cropland in the county was planted in one of these two crops. The largest corn crop was harvested in 1919, when farmers produced 765,420 bushels of corn on 54,517 acres. The largest cotton crop was harvested in 1929, when farmers picked and ginned 22,040 bales of cotton from 90,871 acres. In many ways the majority of farmers in the county were not only growing the crops that had always been grown, but they were also using some of the same methods. Until the 1940s most of the cotton and corn fields in the county were still being cultivated with a mule or team of mules, and the crops were being harvested by hand. In 1940 only fifty-five of the 4,952 farms in the county had tractors, 392 had trucks, and 1,119 had automobiles. Almost 90 percent of the farm houses in the county were not wired for electricity, and more than 90 percent had no telephones. Although the same crops were being produced, with many of the same tools and methods, there were real differences in the lives of the county’s farmers. During the antebellum period the main avenue for moving crops to market had been the Sabine River or a wagon to Marshall, Jefferson, or one of the other larger market centers. In 1885 the Houston East and West Texas Railway was built through the northern portion of the county, and in 1904 the Gulf, Beaumont and Great Northern Railroad was completed, crossing through the center of the county from north to south. These two railroads gave farmers easier and more efficient access to markets. By 1940 roads in the county were being paved, U.S. highways 84, 96, and 59 had been constructed, and trucks were beginning to be used to transport the crops. Wider and more efficient access to markets and the gradual expansion of the county’s cotton crop had not brought prosperity for most of the farmers in the county. Between 1890 and 1930 the number of Shelby County farmers who owned all or a part of the land they farmed steadily fell, dropping from 77 percent in 1890 to 42 percent in 1930.

While agriculture was the foundation of the county’s economic base, the county was never exclusively agricultural. Manufacturing provided jobs for a small portion of the county’s labor force from 1850, when twelve people were employed and products were valued at $6,350. From that point every census recorded a larger number of people employed in industry until 1930, when 707 people were employed to make products valued at $2,048,458. The number of workers employed was small compared to the total population of 28,627, but the income generated had a significant impact on the county’s economy. The population of Shelby County grew steadily during the first four decades of the twentieth century, reaching a peak of 29,235 in 1940. After World War II the population began a long slow decline, as numerous residents left to take advantage of opportunities elsewhere. By 1970 the county’s population had fallen to 19,672, its lowest figure since the 1890s. The drop in the number of inhabitants was particularly in the county’s black population, which declined from a high of 7,522 in 1940 to 4,796 in 1970. After that the county’s population began to grow again, and by 1982 the estimated number of inhabitants was 23,700, a 17 percent gain from 1970. In 1990 the population of the county was 22,034. During the early 1980s almost 75 percent of county residents lived in rural areas. The county’s population also had a high percentage of residents over age sixty-four and a median age of thirty-five, reflecting the continuing outmigration of the young.

Bibliography

George L. Crocket, Two Centuries in East Texas (Dallas: Southwest, 1932; facsimile reprod. 1962). John Warren Love, The Regulator-Moderator Movement in Shelby County, Texas (M.A. thesis, University of Texas, 1936). Patricia R. McCoy, Shelby County Sampler (Lufkin, Texas, 1982). John W. Middleton, History of the Regulators and the Moderators (Fort Worth: Loving, 1883). Mildred Cariker Pinkston, People, Places, Happenings: Shelby County (Center, Texas: Pinkston, 1985). Oran M. Roberts, “The Shelby War, or the Regulators and the Moderators,” Texas Magazine, August 1897. Charles E. Tatum, Shelby County: In the East Texas Hills (Austin: Eakin Press, 1984). Vertical Files, Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.